Share this

Article

You are free to share this article under the Attribution 4.0 International license.

A new finding contradicts previous assumptions about the role of mobile plate tectonics in the development of life on Earth.

Scientists have used tiny mineral crystals called zircons to study plate tectonics billions of years ago. The research sheds light on the conditions that existed in early Earth, revealing a complex interplay among Earth’s crust, core, and the emergence of life.

Plate tectonics allows heat from Earth’s interior to escape to the surface, forming continents and other geological features necessary for life to emerge. Accordingly, “there has been the assumption that plate tectonics is necessary for life,” says John Tarduno, professor of geophysics at the University of Rochester. But new research casts doubt on that assumption.

Tarduno is lead author of a paper in Nature examining plate tectonics from a time 3.9 billion years ago, when scientists believe the first traces of life appeared on Earth. The researchers found that mobile plate tectonics was not occurring during this time. Instead, they discovered, Earth was releasing heat through what is known as a stagnant lid regime. The results indicate that although plate tectonics is a key factor for sustaining life on Earth, it is not a requirement for life to originate on a terrestrial-like planet.

“We found there wasn’t plate tectonics when life is first thought to originate, and that there wasn’t plate tectonics for hundreds of millions of years after,” says Tarduno. “Our data suggests that when we’re looking for exoplanets that harbor life, the planets do not necessarily need to have plate tectonics.”

Clues in zircons

The researchers didn’t set out to study plate tectonics.

“We were studying the magnetization of zircons because we were studying Earth’s magnetic field,” Tarduno says.

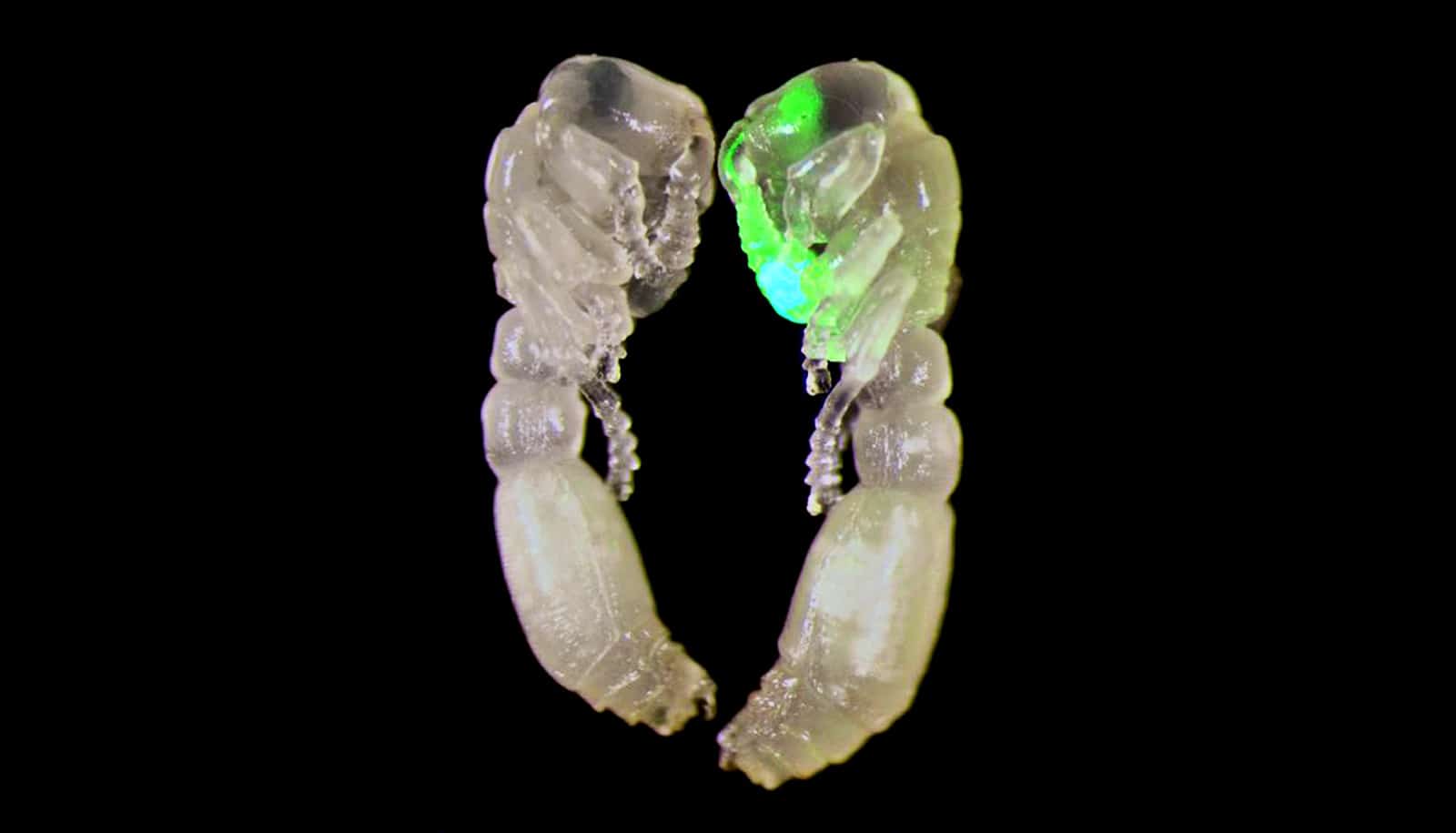

Zircons are tiny crystals containing magnetic particles that can lock in the magnetization of Earth at the time the zircons were formed. By dating the zircons, researchers can construct a timeline tracing the development of Earth’s magnetic field.

The strength and direction of Earth’s magnetic field change depending on latitude. For example, the current magnetic field is strongest at the poles and weakest at the equator. Armed with information about zircons’ magnetic properties, scientists can infer the relative latitudes at which the zircons formed. That is, if the efficiency of the geodynamo—the process generating the magnetic field—is constant and the intensity of the field is changing over a period, the latitude at which the zircons formed must also be changing.

But Tarduno and his team discovered the opposite: the zircons they studied from South Africa indicated that during the period from about 3.9 to 3.4 billion years ago, the strength of the magnetic field did not change, which means the latitudes did not change either.

Because plate tectonics includes changes in latitudes of various land masses, Tarduno says, “plate tectonic motions likely weren’t occurring during this time and there must have been another way Earth was removing heat.”

Further reinforcing their findings, the researchers found the same patterns in zircons they studied from Western Australia.

“We aren’t saying the zircons formed on the same continent, but it looks like they formed at the same unchanging latitude, which strengthens our argument that there wasn’t plate tectonic motion occurring at this time,” Tarduno says.

Stagnant lid tectonics

Earth is a heat engine, and plate tectonics is ultimately the release of heat from Earth. But stagnant lid tectonics—which results in cracks in Earth’s surface—are another means allowing heat to escape from the interior of the planet to form continents and other geological features.

Plate tectonics involves the horizontal movement and interaction of large plates on Earth’s surface. Tarduno and his colleagues report that, on average, plates from the last 600 million years have moved at least 8,500 kilometers (5,280 miles) in latitude. In contrast, stagnant lid tectonics describes how the outermost layer of Earth behaves like a stagnant lid, without active horizontal plate motion. Instead, the outer layer remains in place while the interior of the planet cools. Large plumes of molten material originating in Earth’s deep interior can cause the outer layer to crack. Stagnant lid tectonics is not as effective as plate tectonics at releasing heat from Earth’s mantle, but it can still lead to the formation of continents.

“Early Earth was not a planet where everything was dead on the surface,” Tarduno says. “Things were still happening on Earth’s surface; our research indicates they just weren’t happening through plate tectonics. We had at least enough geochemical cycling provided by the stagnant lid processes to produce conditions suitable for the origin of life.”

Plate tectonics and and other planets

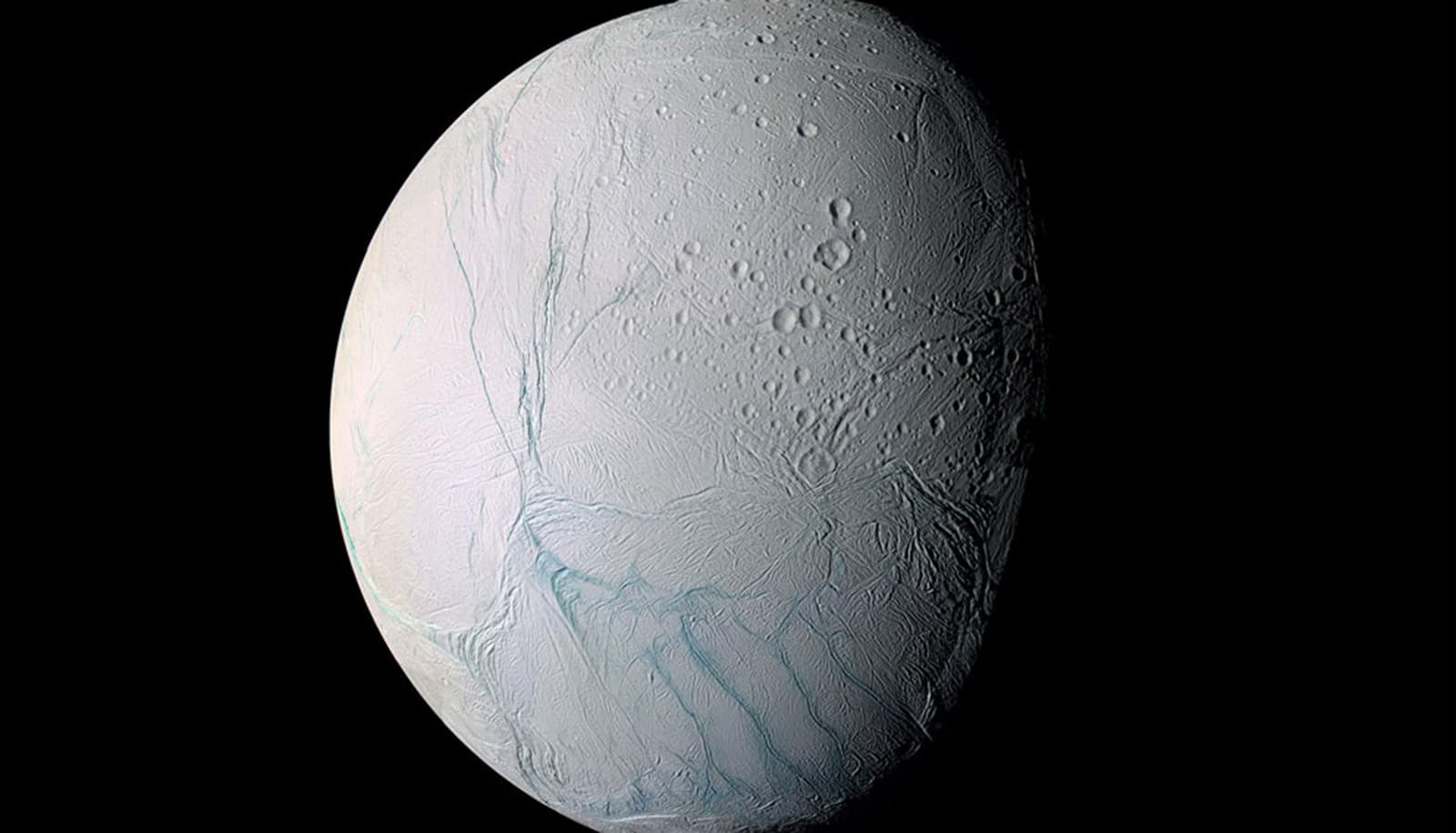

While Earth is the only known planet to experience plate tectonics, other planets, such as Venus, experience stagnant lid tectonics, Tarduno says.

“People have tended to think that stagnant lid tectonics would not build a habitable planet because of what is happening on Venus,” he says. “Venus is not a very nice place to live: it has a crushing carbon dioxide atmosphere and sulfuric acid clouds. This is because heat is not being removed effectively from the planet’s surface.”

Without plate tectonics, Earth may have met a similar fate. While the researchers hint that plate tectonics may have started on Earth soon after 3.4 billion years, the geology community is divided on a specific date.

“We think plate tectonics, in the long run, is important for removing heat, generating the magnetic field, and keeping things habitable on our planet,” Tarduno says. “But, in the beginning, and a billion years after, our data indicates that we didn’t need plate tectonics.”

Funding for the research came from the National Science Foundation.

Source: University of Rochester