NASA is just months away from closing off its data relay satellite fleet to new users in preparation for switching over to commercial alternatives.

Following success in leveraging the private sector to send people and cargo to the International Space Station, the agency’s program for fostering a commercial data relay market for spacecraft users is on the home stretch toward services next decade.

Advances in spacecraft design and cheaper launch costs have led to a proliferation of satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO), opening up new businesses for broadband, Earth observation and other commercial space markets. Satellites in LEO can transfer data with Earth much quicker than those farther away in higher orbits. Being closer to the ground also has its advantages for remote sensing instruments.

However, LEO satellites must also wait until they pass an approved ground station before downloading or uploading data. That’s a growing issue amid a need for not only more data but to have it delivered faster than ever before. Waiting 90 minutes for a satellite to encircle Earth and reconnect with a ground station won’t cut it.

More ground stations and extensive, costly ground infrastructure can help reduce this latency for constellations too sparse to transfer data effectively via inter-satellite links, but are no match for the unstoppable march toward services in real-time.

Still, despite growing demand, the commercial space relay market has a checkered history. Silicon Valley startup Audacy and Australia-owned SpaceLink both collapsed in recent years after failing to get funds to build their constellations from scratch.

RETIREMENT PLAN

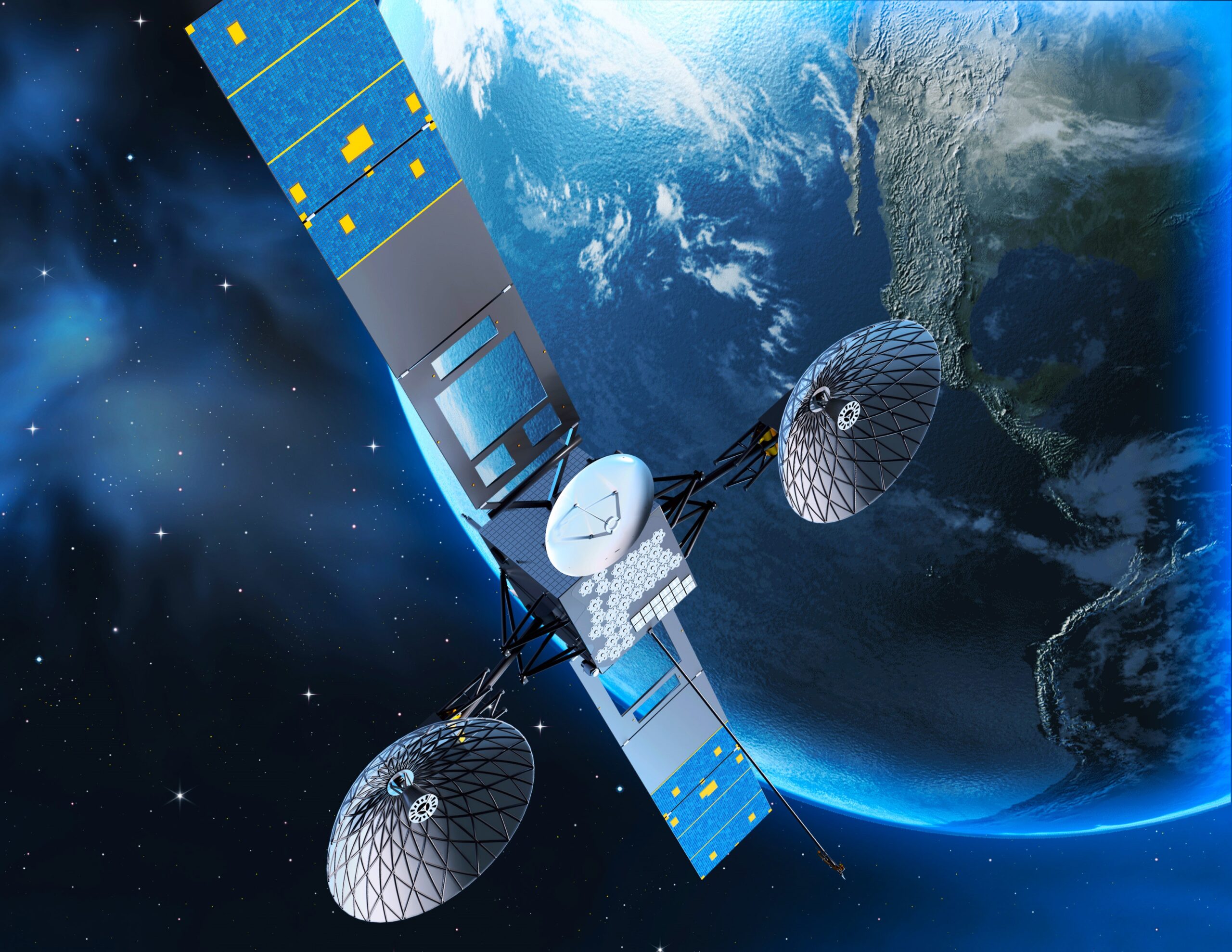

NASA has for decades relied on its own Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) constellation to provide speedy connectivity for government users such as the International Space Station and U.S. Department of Defense.

The agency currently has six of these satellites in service. The oldest of these, TDRS-6, was launched in 1993. The youngest, TDRS-M, was launched in August 2017 and designed to last around 15 years.

To help ensure commercial alternatives will be in place in the coming decade, NASA decided to boost data relay services under development as an ancillary service for constellations with much broader missions.

In June 2022, NASA awarded $278.5 million worth of funded Space Act Agreements to six companies keen to demonstrate services that could replace TDRS and address the agency’s future needs.

“We were pleasantly surprised but pleased we had six of them,” said Thomas Kacpura, deputy project manager for the Communication Services Project (CSP) at NASA’s Glenn Research Center. The group comprises a mix of traditional satellite operators and constellation developers with various capabilities in the works across different orbits.

SpaceX and Amazon’s Kuiper Government Solutions aim to show how their LEO constellations could use optical links to provide communications services for satellites and launches.

The remaining four companies seek to demonstrate similar services using radio frequencies (RF).

Viasat and Inmarsat Government are planning relay services from satellites in geostationary orbit (GEO). Telesat U.S. Services would demonstrate services from GEO and LEO satellites, while SES Government Solutions would use its fleet in GEO and medium Earth orbit (MEO).

Notably, NASA expects the six companies to inject a combined $1.5 billion from their own resources to conduct the demonstrations and prepare for the start of commercial services.

The NASA investment “provides that push over the hump,” Kacpura said during an interview with SpaceNews, helping ensure their relay services are up sooner than they would have taken on their own.

Without getting into specifics, Kacpura said each company is working toward different milestones under a roughly four-to-five-year schedule that would culminate in an operational end-to-end service demonstration.

He said NASA is very pleased with the progress so far and currently anticipates all partners will finish their agreements as planned.

“We’re roughly about at the halfway point,” he said, “where we’re starting to see that the upcoming demonstrations are close.”

He said the companies have currently done multiple “limited types of demonstrations to prove out various aspects of their system, and they are making good progress toward ultimately being able to do that end-to-end operational service demonstration.

“After they complete that, they should be able to turn around and offer the service.”

MORE OPPORTUNITIES

Kacpura said NASA is also talking to “a couple different companies” to set up non-reimbursable Space Act Agreements to share the agency’s needs and get information on other relay systems in development

“Those give us the insight on other industry capabilities that are out there,” he said, declining to name companies because negotiations are ongoing.

Canadian small satellite operator Kepler Communications, which is developing an optical data relay network slated to come online next year, has been vocal about plans to serve government and commercial customers.

Kepler also recently teamed up with Europe’s Airbus Defence and Space and its independent laser terminal subsidiary Tesat-Spacecom to develop a LEO relay network for the European Space Agency’s HydRON program.

HydRON, or High Throughput Optical Network, envisages a multi-orbit, terabit-per-second transport network for extending the reach of fiber networks on the ground.

STATUS CHECK

SES said June 5 it had successfully tested a stable relay link between one of its MEO satellites and a LEO flight-representative terminal on the ground.

That success sets the GEO and MEO operator up to be the first CSP participant to demonstrate a relay link in orbit early next year. Planet, which operates an Earth imagery constellation, is its subcontractor and is due to provide the LEO terminal.

Viasat, which acquired Inmarsat last year, recently announced partnerships with Loft Orbital and Rocket Lab to provide the LEO satellites needed to demonstrate relay terminals with its geostationary fleet in the fall of 2025 and early 2026, respectively. Inmarsat’s first demo is slated for March 2025 and will attempt to provide relay communications for a New Glenn rocket from Blue Origin.

Amazon, due to begin deploying operational Project Kuiper satellites toward the end of 2024 for a proposed LEO broadband constellation of more than 3,000 spacecraft, is working toward its first relay demo in May. SpaceX already has more than 6,000 Starlink broadband satellites in LEO but is waiting for a representative mission launch, so its first relay demo is slated seven months later than Amazon.

SpaceX and Amazon, which are developing their own optical terminals, did not return requests for comments before the press deadline.

ONE SHOE DOES NOT FIT ALL

Established GEO operator Telesat declined to comment on the milestones it expects to reach before its first relay demo in June 2025.

Telesat, which will use a spacecraft from Planet for its first LEO demo, does not expect to begin deploying the 198 satellites in its proposed Lightspeed constellation until 2026. Like Starlink and Project Kuiper, Lightspeed would use optical links to move data across its own network of LEO satellites.

Philip Harlow, president of Telesat Government Solutions, said during a separate interview that the company is looking into offering relay services to LEO customers using optical communications technology in addition to RF links. “It’s not just one or the other,” he said. “NASA is interested in us demonstrating both capabilities.”

“[T]here’s some thought that optical interconnectivity rather than RF interconnectivity is the way forward,” Harlow added, particularly for small satellites where laser communications can deliver more bits for less energy.

RF interconnectivity can be easier to implement and more cost-effective for larger spacecraft.

But while the size, weight and power of the terminal a customer needs to have on their spacecraft to connect with the relay network are important considerations, space relayers must also factor in contact times.

“How often will you be able to contact, how long will those contacts be [and] what is the acquisition time?” Harlow continued.

“And then given those three factors, what does the connection speed look like? Because it varies by distance, length of time and things like that.”

SEEDING THE MARKET

Prospective space relayers are banking on these commercial opportunities being attractive enough for customers to install compatible antennas on their satellites, even as commercial relay networks are still years away from entering service.

“The adoption of this is kind of gestational,” Harlow said, adding: “Certainly my wife would never wait for three years before she got the benefit of something she spent a lot of money on … there’s this build it and they will come kind of mentality [and] you’ve got to foster that desire in the customer.”

Although the CSP program helpssmooth the way for these conversations with NASA, other government agencies and commercial customers outside thiscommercialization effort have proved far more challenging.

FUTURE NASA NEEDS

When NASA selected out the CSP awards two years ago, it looked like the TDRS service would need to be retired in the 2030s.

“The predictions right now point out that the remaining satellites should be good into the 2040 timeframe,” according to Kacpura.

That’s good news for legacy TDRS users. The relay satellites serviced more than 30 NASA missions in May. However, Kacpura said NASA plans to formally begin transitioning to commercial relay services for new missions around August when the agency will close off TDRS to new users.

And while the agency anticipates several high-intensity users will leave the network as their missions end in parallel with the TDRS fleet’s gradual retirement, demand from new users remains strong.

“We anticipate demand for relay services will continue; new science missions will be studying an array of transient events and executing missions that require near-real-time coordination of assets,” Greg Heckler, program executive for commercialization at NASA’s Space Communication and Navigation Program, said via email.

“Space relay is ideal for these “on-demand” and low latency science operations, and human space flight is a major driver of this demand.”

He said the follow-on to the International Space Station, which will also see NASA leverage an emerging commercial market, will need relay services, as will emergent human spaceflight programs globally.

NASA’s Artemis Moon exploration program will also present ongoing needs for near-Earth relay to support LEO operations.

“As NASA learns to embrace emerging capabilities in the commercial market, we anticipate new opportunities will arise beyond just high data rate and low latency communications,” Heckler continued.

NEXT STEPS

While NASA already has sufficient funding to complete the CSP demonstrations, Kacpura said follow-on steps are currently being considered as the agency drafts its 2026 budget request.

After concluding the Space Act Agreements, he said NASA would need to fully validate the services it would acquire through a fair and open competition process to ensure they can support missions that tend to have long durations. And although international regulators recently allocated radio frequencies in Ka-band for space-to-space communications, Kacpura said more work needs to be done to clear relay services in L-band and C-band.

This article first appeared in the July 2024 issue of SpaceNews Magazine.

Related