HELSINKI — Azerbaijan signed up to China’s International Lunar Research Station project Tuesday, on the sidelines of a major international space conference.

Li Guoping, chief engineer of the China National Space Administration (CNSA) and Samaddin Asadov, chairman of the Board of Azercosmos, Azerbaijan’s space agency, signed a joint statement on cooperation on the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) Oct. 3 during the 74th International Astronautical Congress (IAC), hosted by Azerbaijan, in the capital Baku. CNSA announced the agreement Oct. 8 via a statement on its webpages.

The agreement, as with a statement released on South Africa joining the ILRS last month, does not provide specifics of the cooperation.

The statement said the agreement will see CNSA and Azercosmos carry out extensive cooperation in the demonstration, implementation, operation and application of the ILRS, as well as training and other areas.

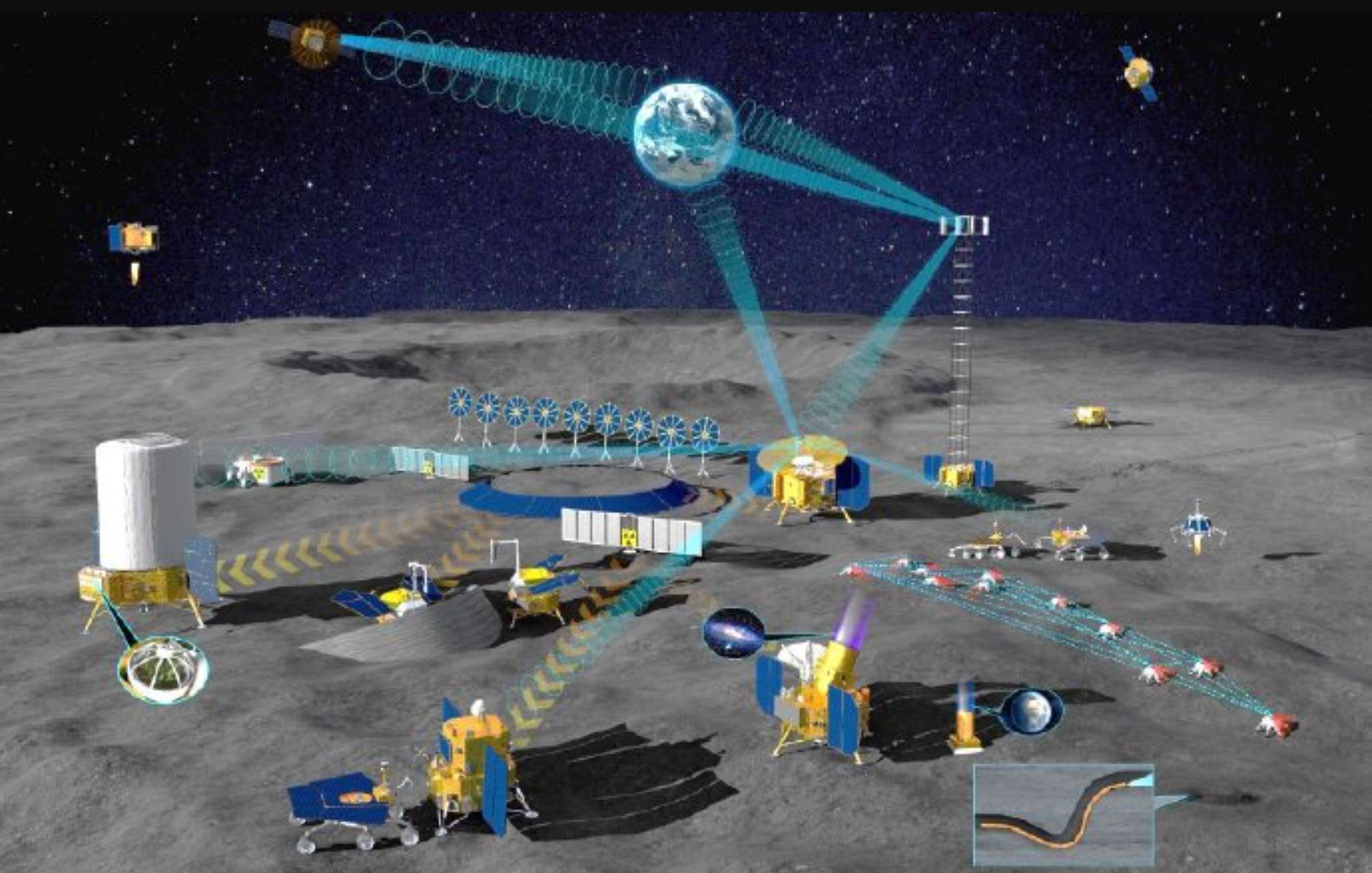

The ILRS project aims to construct a permanent lunar base in the 2030s. The initiative is seen as a China-led, parallel project and potential competitor to the NASA-led Artemis Program.

China has now attracted around 15 signatories to its ILRS initiative, according to representatives of the Deep Space Exploration Laboratory (DSEL) under the CNSA. However, a list of these partners is not yet available. The partners are known to consist of organizations and institutions as well as countries.

Russia, Venezuela and South Africa have signed up. The Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization (APSCO), Swiss firm nanoSPACE AG, the Hawaii-based International Lunar Observatory Association (ILOA), and the National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand (NARIT) have also signed joint statements. Pakistan is also thought to have signed up.

China and Russia presented a joint ILRS roadmap in 2021 in St. Petersburg. Beijing has however since apparently taken the role of lead of the project since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

China is setting up an organization, named ILRSCO, in the city of Hefei in Anhui province to coordinate the initiative. DSEL said earlier this year that China aims to complete the signing of agreements with space agencies and organizations for founding members of ILRSCO by October.

Meanwhile, the U.S. is growing the number of signatories to its Artemis Accords. Last month Germany became the 29th country to sign up to the Accords, the political underpinning of the Artemis lunar program.

The Accords have signatories from each continent. A working group from the Accords stated at IAC that it drafted ideas to boost transparency in lunar cooperation.

China is already working on a series of robotic missions to launch later this decade as precursors to the ILRS. The 2026 Chang’e-7 lunar south pole mission and 2028 Chang’e-8 in-situ resource utilization and 3D-printing technology test mission will lay the basis for the larger plan, according to CNSA. NARIT will be involved in Chang’e-7 through the Sino-Thai Sensor Package for Space Weather Global Monitoring payload.

China will next year also launch Chang’e-6, which will be a first-ever lunar far side sample return mission. Pakistan will be involved in a CubeSat to fly with the mission.

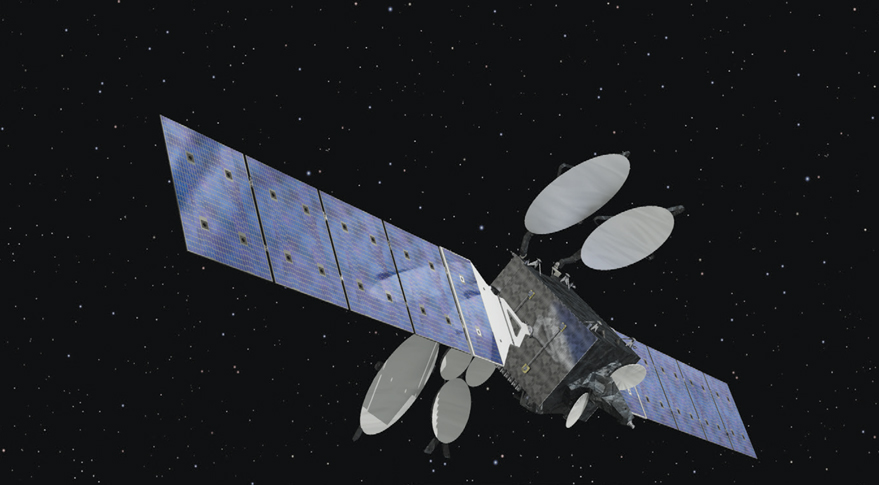

A relay satellite named Queqiao-2 will be launched ahead of that mission early in 2024. The Queqiao-2 satellite will provide communications support for the Chang’e-6, 7 and 8 missions.

Russia’s Luna 25 mission was nominally part of the ILRS. That mission launched in August this year, but crashed into the moon during an anomalous orbital maneuver.

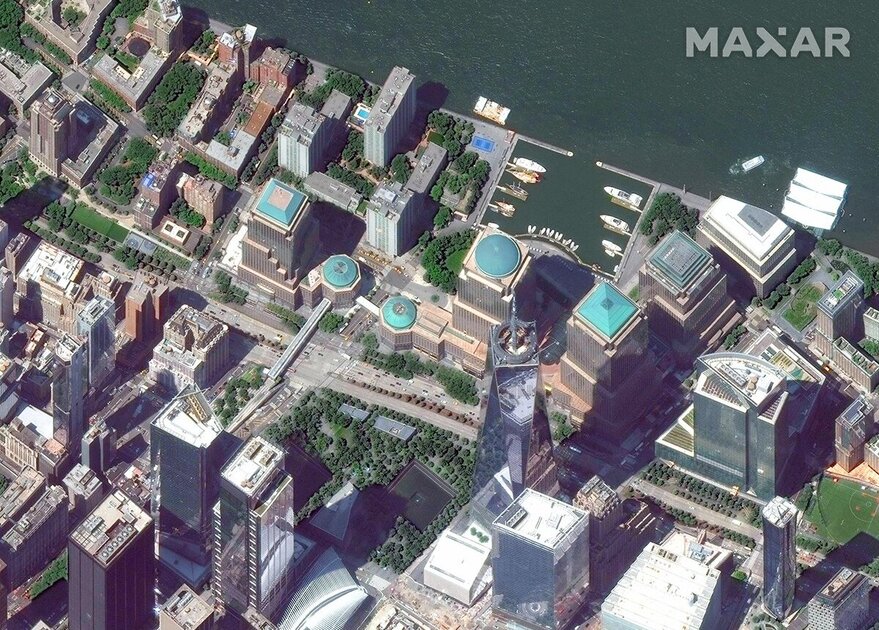

Azercosmos was founded in 2010. It operates a pair of telecommunications satellites, while communication with its only remote sensing satellite, Azersky, launched in 2014, was lost in April this year. Chinese commercial telemetry, tracking and command firm Emposat operates two ground stations in Azerbaijan.