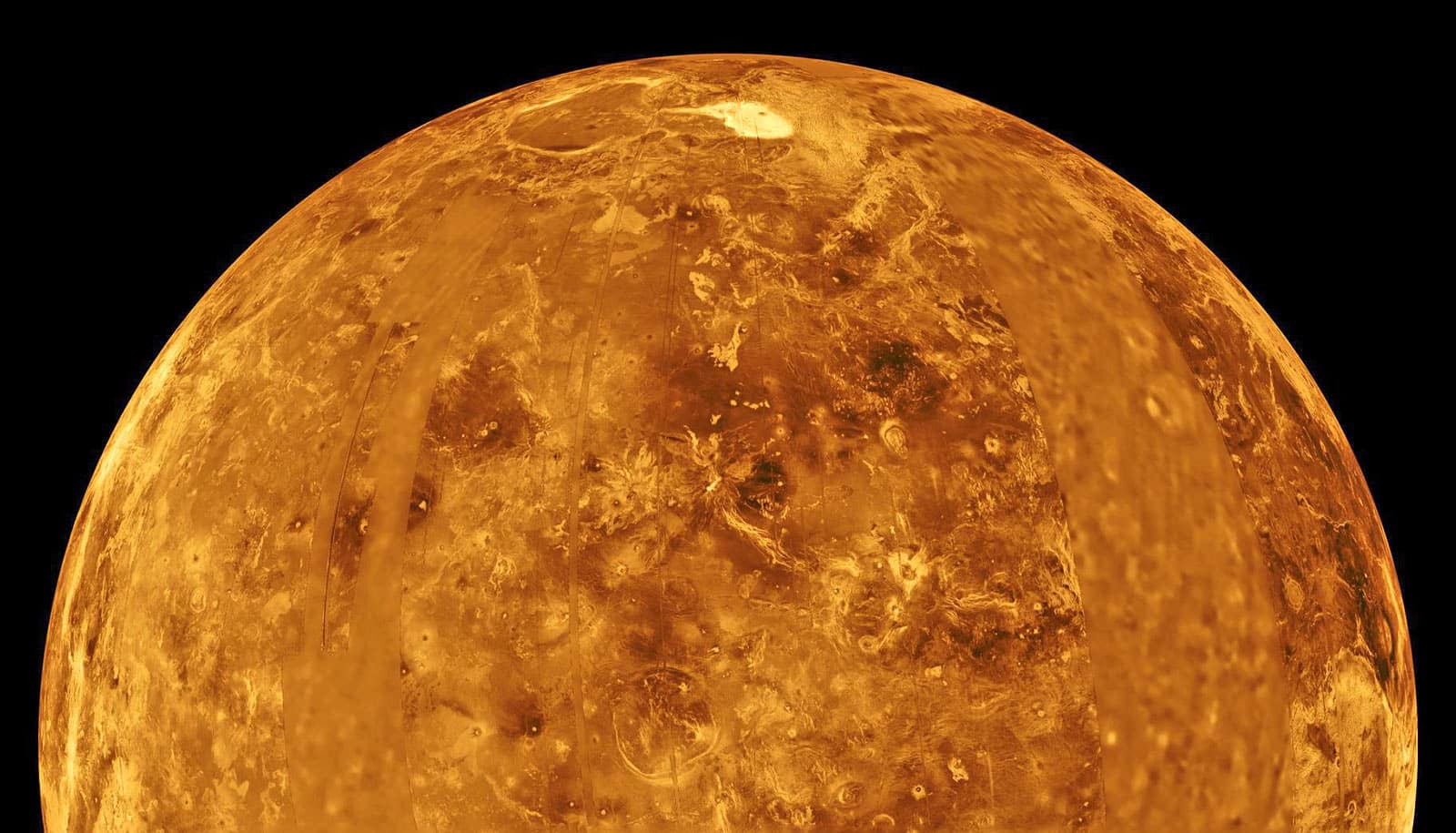

Venus, a scorching wasteland of a planet according to scientists, may have once had tectonic plate movements similar to those believed to have occurred on early Earth, a new study shows.

The finding sets up tantalizing scenarios regarding the possibility of early life on Venus, its evolutionary past, and the history of the solar system.

Researchers describe using atmospheric data from Venus and computer modeling to show that the composition of the planet’s current atmosphere and surface pressure would only have been possible as a result of an early form of plate tectonics, a process critical to life that involves multiple continental plates pushing, pulling, and sliding beneath one another.

Planetary neighbors

On Earth, this process intensified over billions of years, forming new continents and mountains, and leading to chemical reactions that stabilized the planet’s surface temperature, resulting in an environment more conducive to the development of life.

Venus, on the other hand, Earth’s nearest neighbor and sister planet, went in the opposite direction and today has surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead. One explanation is that the planet has always been thought to have what’s known as a “stagnant lid,” meaning its surface has only a single plate with minimal amounts of give, movement, and gasses being released into the atmosphere.

The new paper posits that this wasn’t always the case. To account for the abundance of nitrogen and carbon dioxide present in Venus’ atmosphere, the researchers conclude that Venus must have had plate tectonics sometime after the planet formed, about 4.5 billion to 3.5 billion years ago.

The paper suggests that this early tectonic movement, like on Earth, would have been limited in terms of the number of plates moving and in how much they shifted. It also would have been happening on Earth and Venus simultaneously.

“One of the big picture takeaways is that we very likely had two planets at the same time in the same solar system operating in a plate tectonic regime—the same mode of tectonics that allowed for the life that we see on Earth today,” says study lead author Matt Weller, who completed the work while he was a postdoctoral researcher at Brown University and is now at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston.

This bolsters the possibility of microbial life on ancient Venus and shows that at one point the two planets—which are in the same solar neighborhood, are about the same size, and have the same mass, density, and volume—were more alike than previously thought before diverging.

The work also highlights the possibility that plate tectonics on planets might just come down to timing—and therefore, so may life itself.

“We’ve so far thought about tectonic state in terms of a binary: it’s either true or it’s false, and it’s either true or false for the duration of the planet,” says coauthor Alexander Evans, an assistant professor of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences at Brown. “This shows that planets may transition in and out of different tectonic states and that this may actually be fairly common. Earth may be the outlier. This also means we might have planets that transition in and out of habitability rather than just being continuously habitable.”

Insights into Venus’ past

That concept will be important to consider as scientists look to understand nearby moons—like Jupiter’s Europa, which has shown proof of having Earth-like plate tectonics—and distant exoplanets, according to the paper.

The researchers initially started the work as a way to show that the atmospheres of far-off exoplanets can be powerful markers of their early histories, before deciding to investigate that point closer to home.

They used current data on Venus’ atmosphere as the endpoint for their models and started by assuming Venus has had a stagnant lid through its entire existence. Quickly, they were able to see that simulations recreating the planet’s current atmosphere didn’t match up with where the planet is now in terms of the amount nitrogen and carbon dioxide present in the current atmosphere and its resulting surface pressure.

The researchers then simulated what would have had to happen on the planet to get to where it is today. They eventually matched the numbers almost exactly when they accounted for limited tectonic movement early in Venus’ history followed by the stagnant lid model that exists today.

Overall, the team believes the work serves as a proof of concept regarding atmospheres and their ability to provide insights into the past.

“We’re still in this paradigm where we use the surfaces of planets to understand their history,” Evans says. “We really show for the first time that the atmosphere may actually be the best way to understand some of the very ancient history of planets that is often not preserved on the surface.”

Upcoming NASA DAVINCI missions, which will measure gasses in the Venusian atmosphere, may help solidify the study’s findings. In the meantime, the researchers plan to delve deep into a key question the paper raises: What happened to plate tectonics on Venus?

The theory in the paper suggests that the planet ultimately became too hot and its atmosphere too thick, drying up the necessary ingredients for tectonic movement.

“Venus basically ran out of juice to some extent, and that put the brakes on the process,” says coauthor Daniel Ibarra, a professor in the Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences department.

The researchers say the details of how this happened may hold important implications for Earth.

“That’s going to be the next critical step in understanding Venus, its evolution, and ultimately the fate of the Earth,” Weller says. “What conditions will force us to move in a Venus-like trajectory, and what conditions could allow the Earth to remain habitable?”

The paper appears in Nature Astronomy. Alexandria Johnson from Purdue University is a coauthor. NASA’s Solar System Workings program supported the work.

Source: Brown University