Share this

Article

You are free to share this article under the Attribution 4.0 International license.

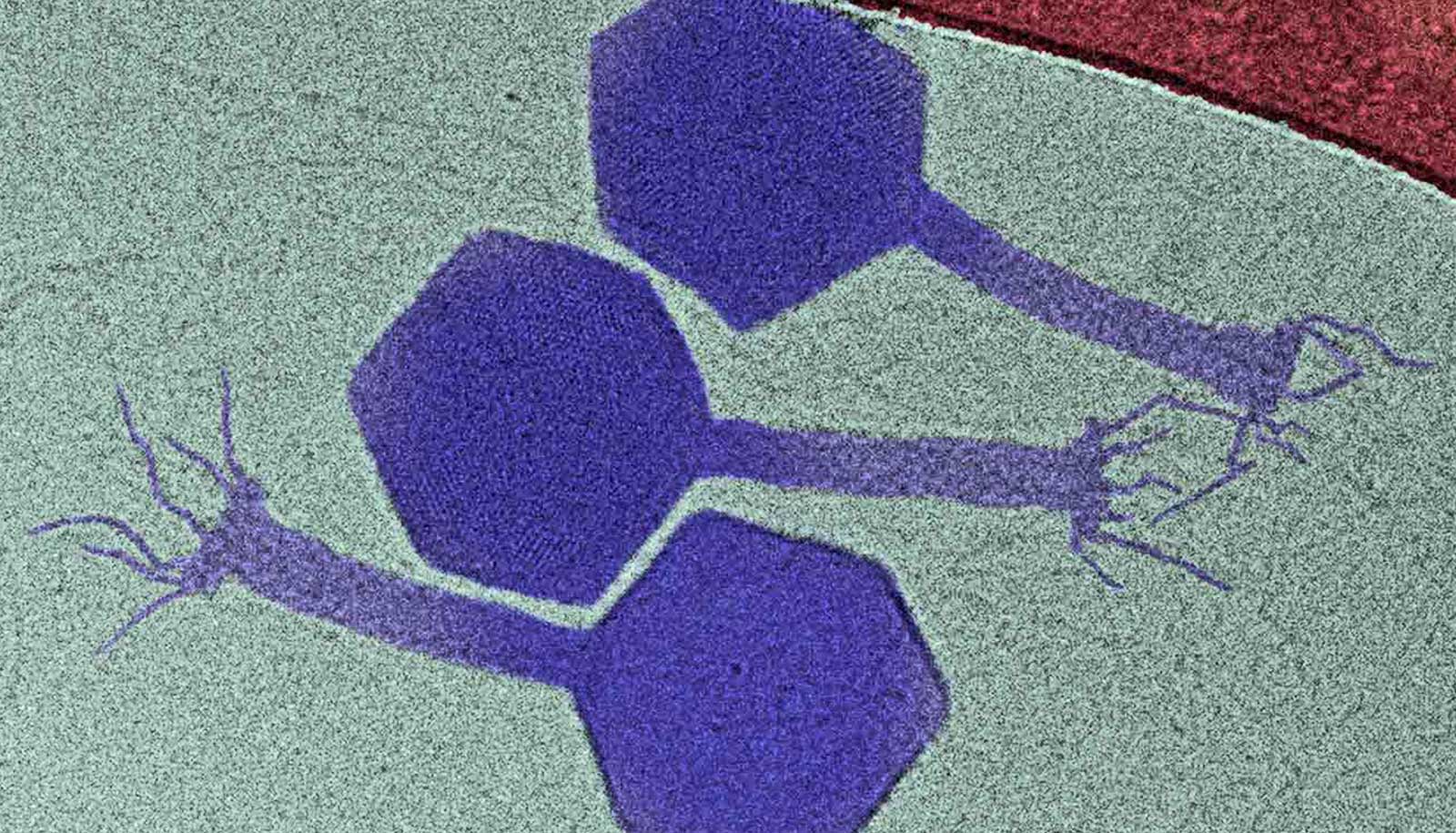

Researchers have found a virus that can kill dormant bacteria.

The discovery could help fight germs that can’t be treated with antibiotics alone.

In nature, most bacteria live on the bare minimum. If they experience nutrient deficiency or stress, they shut down their metabolism in a controlled manner and go into a resting state. In this stand-by mode, certain metabolic processes still take place that enable the microbes to perceive their environment and react to stimuli, but growth and division are suspended.

This also protects bacteria from, say, antibiotics or from viruses that prey exclusively on bacteria. Such bacteria-infecting viruses, known as phages, are considered a possible alternative to antibiotics that are no longer (sufficiently) effective due to drug resistance.

Until now, expert consensus held that phages successfully infect bacteria only when the latter are growing.

Researchers at ETH Zurich asked themselves whether evolution might have produced bacteriophages that specialize in dormant bacteria and could be used to target them. They began their search in 2018.

Now, a new study published in Nature Communications shows that such phages, though rare, do indeed exist.

Compost heap discovery

When Alexander Harms, a professor at ETH Zurich, and his team at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel began their project in 2018, they assumed that within the first year, they would be able to isolate around 20 different phages that attack dormant bacteria. But this wasn’t the case: it wasn’t until 2019 that Harms’ doctoral student Enea Maffei isolated a new, previously unknown virus.

Found in rotting plant material from a cemetery near Riehen (Canton of Basel-Stadt), this virus can infect and destroy dormant bacteria.

“This is the first phage described in the literature that has been shown to attack bacteria in a dormant state,” Maffei says.

“In view of the huge number of bacteriophages, however, I was always convinced that evolution must have produced some that can crack into dormant bacteria,” Harms says. The researchers named their new phage Paride.

Taking sleeping bacteria by surprise

The virus the researchers found infects Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacterium commonly found in many environments. Various strains colonize bodies of water, plants, the soil—and people. In the human body, certain strains can cause serious respiratory diseases such as pneumonia, which can be fatal.

“We’re just at the beginning. The one thing we know for sure is that we know almost nothing.”

How the new phage takes dormant P. aeruginosa germs by surprise, however, is not yet clear to the researchers. They suspect that the virus uses a specific molecular key to awaken the bacteria, and then hijacks the cell’s multiplication machinery for its own reproduction. However, the researchers have not yet been able to clarify exactly how this works.

They thus aim to elucidate the genes or molecules that underlie this awakening mechanism. Based on this, they could develop substances in a test tube that take over the wake-up process. Such a substance could then be combined with a suitable antibiotic that completely eliminates the bacteria.

“But we’re just at the beginning. The one thing we know for sure is that we know almost nothing,” Harms says.

Better together

To test the efficacy of the Paride phage, the researchers paired it with an antibiotic called meropenem. This disrupts cell wall synthesis and so it interferes only with cellular processes that don’t damage the phages. The antibiotic has no effect on dormant bacteria, as these don’t synthesize a new cell wall.

When tested in cell culture dishes, the virus was able to kill 99% of all dormant bacteria but left 1% alive. Only the combination of Paride phages and meropenem was able to eradicate the bacterial culture completely, even though the latter had no detectable effect on its own.

In a further experiment together with Nina Khanna, a doctor at Basel University Hospital, Maffei tested this combination on mice with a chronic infection. Neither the phage nor the antibiotic alone worked particularly well in the mice, but the interaction between phages and antibiotics proved to be very effective in living organisms as well.

“This shows that our discovery is not just a laboratory artifact, but could also be clinically relevant,” Maffei says.

Can phages replace antibiotics?

Experts have been discussing phage therapy intensively for many years. Researchers and physicians hope that one day they will be able to use phages to replace antibiotics that have become ineffective. However, broad applications are still lacking, as there have not been any comprehensive studies.

“What we have at present is mostly individual case studies,” Harms says.

Studies by researchers at the Queen Astrid Military Hospital in Brussels showed that the treatment improved the condition of three-quarters of patients and that it was able to eliminate the bacteria in 61%. However, this also means that in four out of 10 patients, the germs could not be removed with phage therapy, even though the bacteria in question were phage-sensitive in the lab.

“This may be because many bacteria in the body are in a dormant state, especially in the case of chronic infections, and so phages can’t penetrate them,” Harms says. Dormant bacteria could also play an important role in infections with non-resistant strains.

“In the case of infections, that means it would be important to know the physiological state of the bacteria in question. Then the right phages, combined with antibiotics, could be used in a targeted manner. However, you need to know exactly how a phage attacks a bacterium before you can select the right phages for a particular treatment. This hasn’t happened yet because we still know too little about the phages,” Harms explains.

That’s why in the years ahead, the researchers will investigate precisely how the new phage brings bacteria out of deep sleep, infects them, and makes them susceptible to antibiotics.

An SNSF Starting Grant to Alexander Harms and NCCR AntiResist funded the work.

Source: ETH Zurich