New images from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope reveal for the first time galaxies with stellar bars at a time when the universe was a mere 25% of its present age.

“I took one look at these data, and I said, ‘We are dropping everything else!’”

Stellar bars are elongated features of stars stretching from the centers of galaxies into their outer disks.

The finding of so-called barred galaxies, similar to our Milky Way, this early in the universe will require astrophysicists to refine their theories of galaxy evolution.

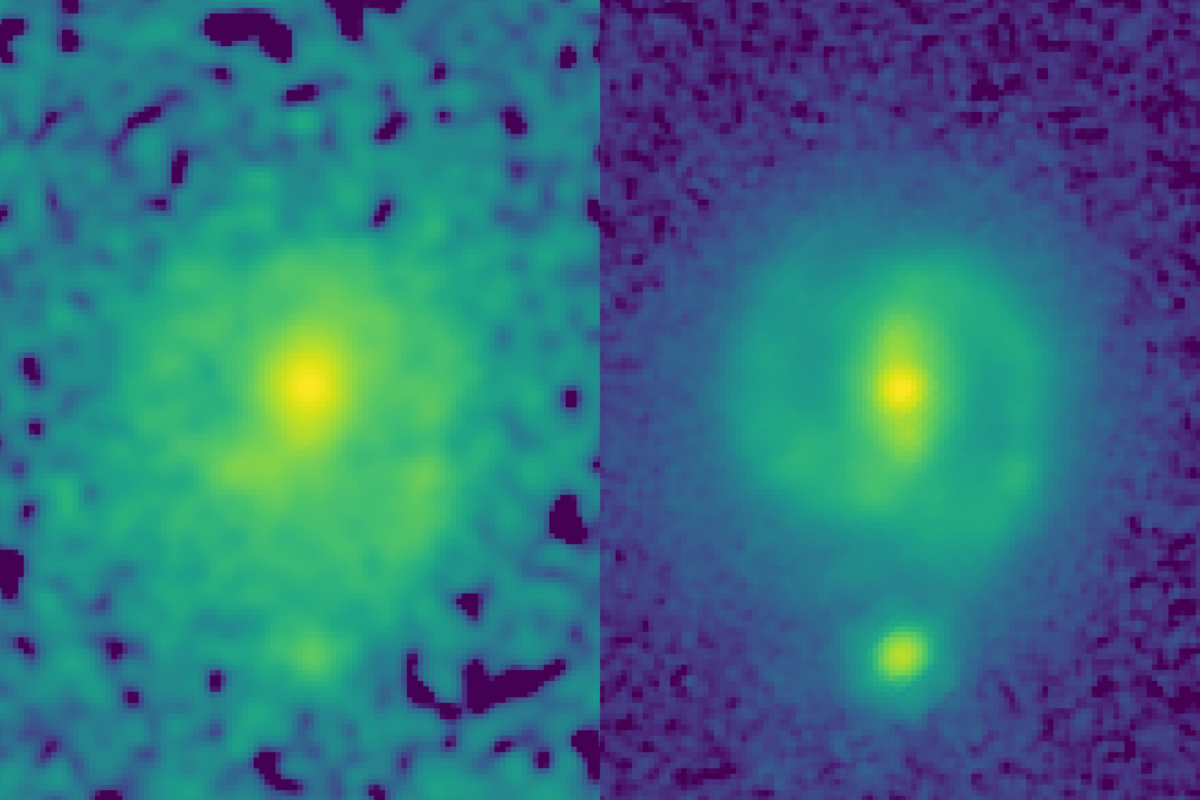

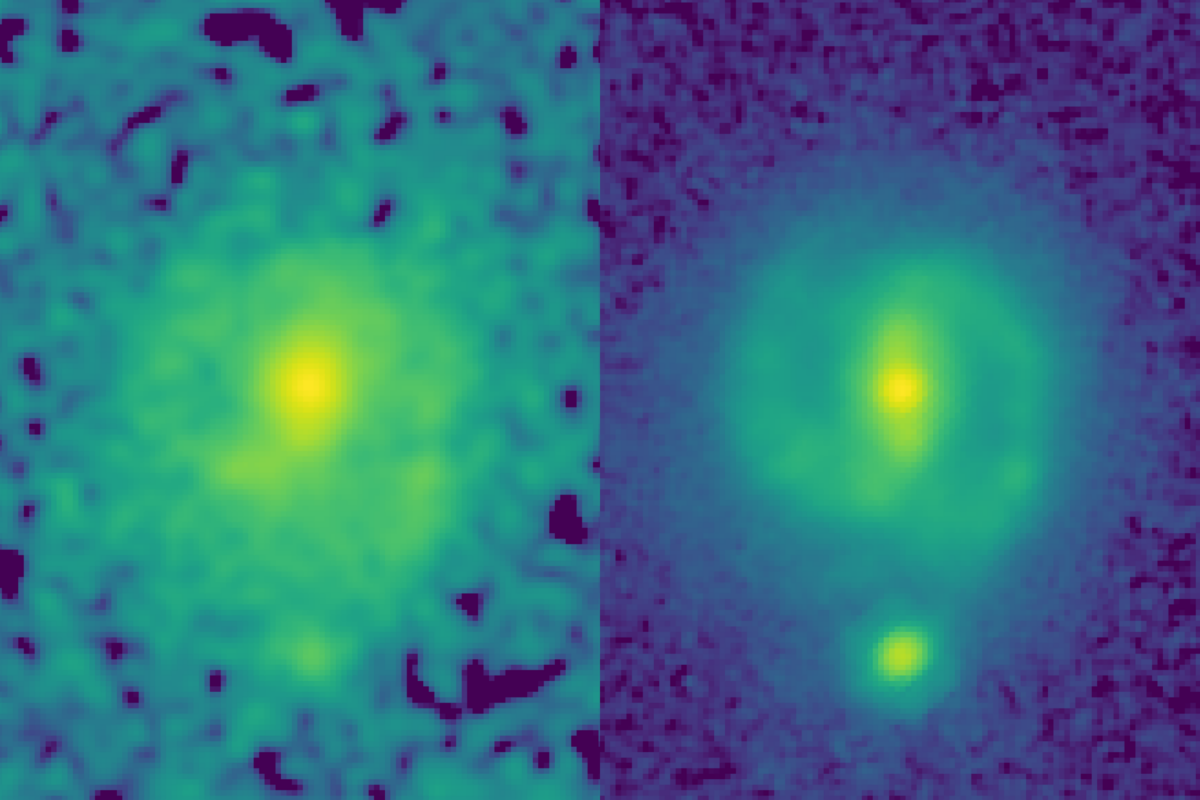

Prior to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), images from the Hubble Space Telescope had never detected bars at such young epochs. In a Hubble image, one galaxy, EGS-23205, is little more than a disk-shaped smudge, but in the corresponding JWST image taken this past summer, it’s a beautiful spiral galaxy with a clear stellar bar.

“I took one look at these data, and I said, ‘We are dropping everything else!’” says Shardha Jogee, professor of astronomy at the University of Texas at Austin.

“The bars hardly visible in Hubble data just popped out in the JWST image, showing the tremendous power of JWST to see the underlying structure in galaxies,” she says, describing data from the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey (CEERS), led by UT Austin professor, Steven Finkelstein.

“It’s like going into a forest that nobody has ever gone into.”

The team identified another barred galaxy, EGS-24268, also from about 11 billion years ago, which makes two barred galaxies existing farther back in time than any previously discovered.

In an article accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, they highlight these two galaxies and show examples of four other barred galaxies from more than 8 billion years ago.

“For this study, we are looking at a new regime where no one had used this kind of data or done this kind of quantitative analysis before,” says Yuchen “Kay” Guo, a graduate student who led the analysis, “so everything is new. It’s like going into a forest that nobody has ever gone into.”

Bars play an important role in galaxy evolution by funneling gas into the central regions, boosting star formation.

“Bars solve the supply chain problem in galaxies,” Jogee says. “Just like we need to bring raw material from the harbor to inland factories that make new products, a bar powerfully transports gas into the central region where the gas is rapidly converted into new stars at a rate typically 10 to 100 times faster than in the rest of the galaxy.”

Bars also help to grow supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies by channeling the gas part of the way.

The discovery of bars during such early epochs shakes up galaxy evolution scenarios in several ways.

“This discovery of early bars means galaxy evolution models now have a new pathway via bars to accelerate the production of new stars at early epochs,” Jogee says.

And the very existence of these early bars challenges theoretical models as they need to get the galaxy physics right in order to predict the correct abundance of bars. The team will be testing different models in their next papers.

JWST can unveil structures in distant galaxies better than Hubble for two reasons: First, its larger mirror gives it more light-gathering ability, allowing it to see farther and with higher resolution. Second, it can see through dust better as it observes at longer infrared wavelengths than Hubble.

Undergraduate students Eden Wise and Zilei Chen played a key role in the research by visually reviewing hundreds of galaxies, searching for those that appeared to have bars, which helped narrow the list to a few dozen for the other researchers to analyze with a more intensive mathematical approach.

Additional coauthors are from UT Austin and other institutions in the US, the UK, Japan, Spain, France, Italy, Australia, and Israel.

Funding for this research came from, in part, the Roland K. Blumberg Endowment in Astronomy, the Heising-Simons Foundation, and NASA. This work relied on resources at the Texas Advanced Computing Center.

Source: UT Austin