Try moderation, not panic, in response to recent news about aspartame, an expert advises.

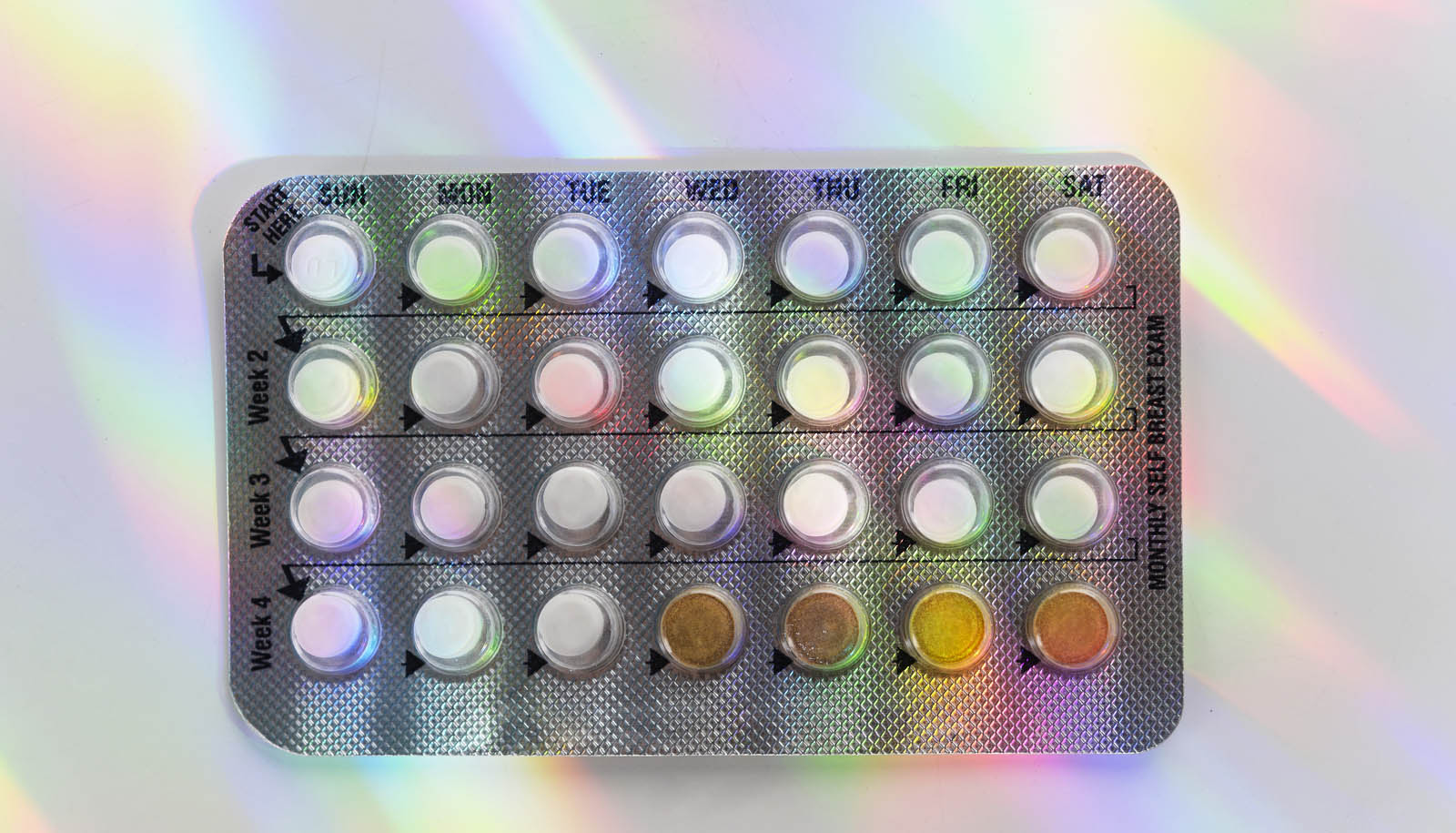

The World Health Organization has added aspartame, the chemical that gives products like Diet Coke their distinctly sweet flavor, to its list of potential carcinogens.

The decision came from the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), which declared that there is some limited evidence linking aspartame with cancer development in humans. That puts the popular sweetener in the same category as aloe vera extract and certain types of pickled vegetables.

Still, even if the link between aspartame intake and cancer is a tenuous one, Meghan Windham, a registered dietician with Texas A&M University Health Services, says there are plenty of other reasons to consider cutting back on aspartame and other artificial sweeteners.

“If someone likes to have a diet soda occasionally, that’s not a big deal,” Windham says. “But if we’re drinking 12 of them a day, that’s probably not the best choice, regardless of whether it’s carcinogenic or not.”

Here, she explains what’s behind the ruling, and stresses that, as with all things, moderation is key.

What does the aspartame classification mean?

IARC sorts carcinogens and potential carcinogens into several different categories:

- Group 1: Carcinogenic to humans

- Group 2A: Probably carcinogenic to humans

- Group 2B: Possibly carcinogenic to humans

- Group 3: Not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity in humans

The agency has placed aspartame in the less risky “possibly carcinogenic” category, meaning evidence for its cancer-causing properties remains limited. Still, Windham says, that doesn’t mean IARC’s declaration should be entirely discounted.

“Certainly there’s a need to be concerned if something like this is coming out,” she says. “I work with a lot of students, and that’s a question I get a lot: ‘Should I be having these artificially sweetened products?’ So I think there’s always been some level of concern, and this is just bringing it into the spotlight.”

But do I have to give up diet soda?

Following IARC’s announcement, the Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives—a group composed of scientists from the WHO and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations—announced guidelines for how much aspartame a person can consume safely.

According to their figures, one’s daily intake of the artificial sweetener should not exceed 40 milligrams per kilogram of body weight. That means a person weighing 150 pounds could consume around a dozen diet sodas a day and still be considered safe, at least as far as cancer risk is concerned.

Windham’s advice? Don’t even get near that number.

“Too much of anything is not a good thing,” she says. “Just because 12 diet drinks a day is ‘safe,’ that’s not the best choice nutritionally. When we think about sugared beverages in general, whether they’re sweetened with stevia, truvia, sucralose, aspartame, or even actual sugar, nutritionally there’s not much there. There’s usually no protein, no healthy fats, they’re not fiber rich. So if we’re just drinking those all day to sustain us, that’s probably not the best.”

Still, she says, that doesn’t mean anyone should have to go cold turkey on artificially sweetened beverages. Just like with processed meats containing nitrates and nitrites—which the WHO classifies in the higher category of “probably carcinogenic”—there’s typically nothing wrong with consuming these products occasionally.

“I always say everything in moderation,” Windham says. “Ideally, we should focus on good old water, low fat milk, and other hydration sources that don’t have sugar or any type of artificial sweetener in them.

“But when we have populations, maybe a type 2 diabetic or someone with a medical condition where they need to choose lower levels of actual sugar, some of these diet drinks are beneficial for them. So I encourage it in those populations who maybe want to take a step down from regular sugared beverages.”

Source: Luke Henkhaus for Texas A&M University