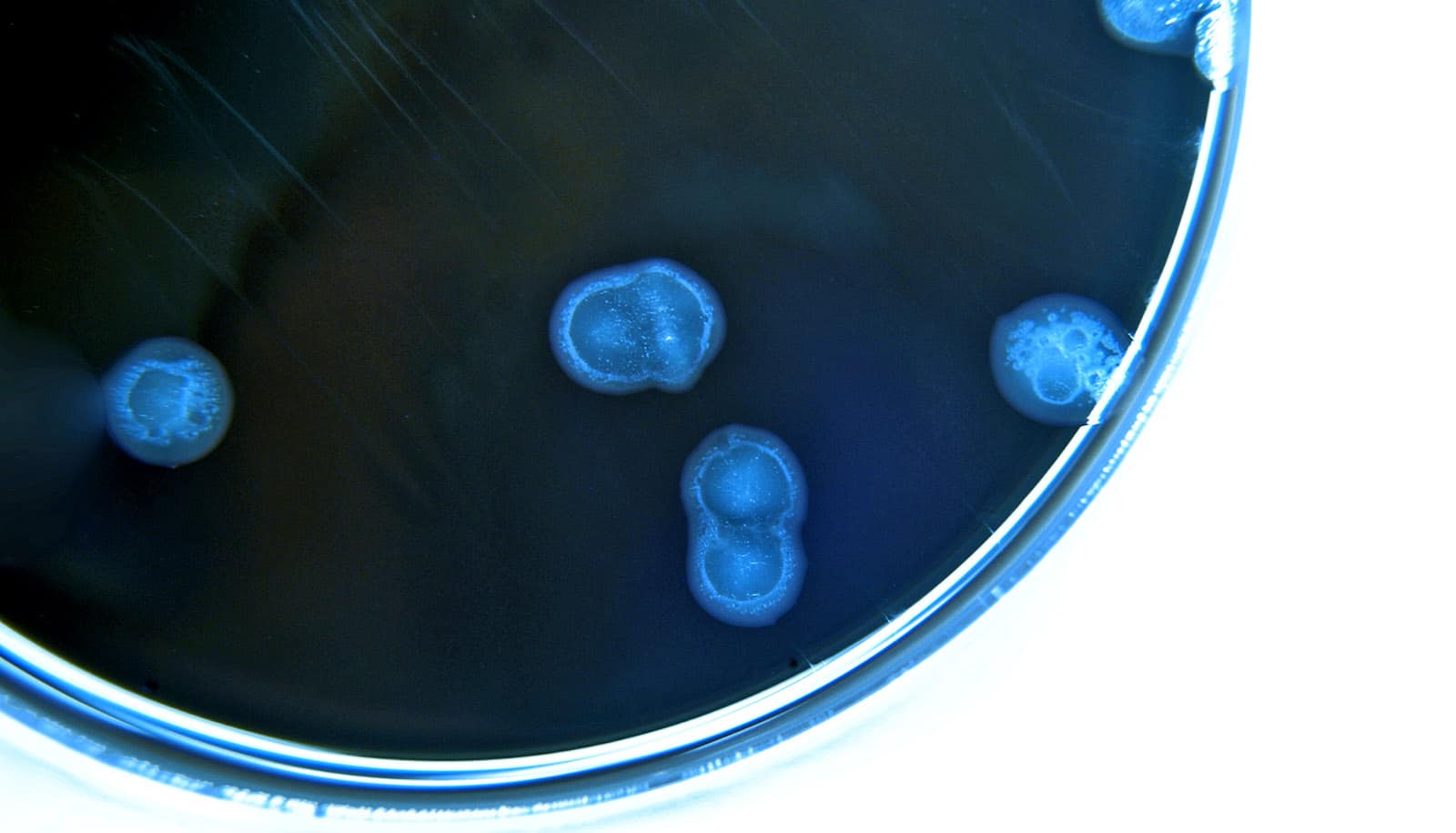

Research finds that antibiotic resistance genes are prevalent in the bacterium Campylobacter jejuni, a leading cause of food borne illness.

The team finds that more than half of the C. jejuni, isolated from patients in Michigan, are genetically protected against at least one antibiotic used to fight bacterial infections. The team’s full report appears in the journal Microbial Genomics.

“We know these pathogens have been around forever but using more sophisticated genome sequencing tools lets us look at them differently,” says Shannon Manning, project leader and a professor in the department of microbiology and molecular genetics at Michigan State University. “We found that the genomes are extremely diverse and contain a lot of genes that can protect them from numerous antibiotics.”

The team’s report provides valuable technical insights to epidemiologists, health care workers, and other specialists, but Manning also emphasizes what the team’s findings mean for the average person.

Although most otherwise healthy adults can fight off such stomach bugs without antibiotics, she says, there are people for whom C. jejuni presents a serious concern. Infections can lead to hospitalization, autoimmune and neurological complications, long-term disability, and even death.

Understanding the extent of antibiotic resistance in this species, as well as which antibiotics different strains are resistant to, can help put patients on better treatment plans sooner.

“If we know the type of antibiotic resistance genes that Campylobacter has, then we know which antibiotics not to give a patient,” Manning says. This can lead to better patient outcomes and shorter hospital stays.

The finding also has broader implications. After people fight off an infection and the pathogen is killed—with or without antibiotics—its genes can linger, including those that provide antibiotic resistance. Other microbes can then pick up those genes, integrate them into their own genomes, and gain resistance.

“That’s really important. Food borne pathogens are ubiquitous. They are found in the foods we eat but also in animals and environments that we come into contact with regularly,” Manning says. “If they carry resistance genes, then not only can they make us sick, but they can also easily transfer the genes to other bacteria.”

This underscores the importance of food hygiene and safety, Manning says, including avoiding cross-contamination of other foods and surfaces before cooking.

The team’s genetic analysis also let the researchers pinpoint the host, or source, of specific strains. That is, they could predict whether the bacteria originated from specific animals or were generalists that are commonly found in multiple hosts.

“When we did this genomic analysis, we found that most patients in Michigan were infected with strains linked to chicken or cattle hosts,” Manning says. Infections also were more likely to occur in rural areas, the team found, suggesting that exposure to these animals and their environments could be important to monitor and potentially control.

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention operates a nationwide network surveilling food borne pathogens, many states, including Michigan, are not part of this system.

“We have unique ecological and agricultural factors in Michigan that may impact how these pathogens survive and proliferate in certain hosts and environments,” says Manning, whose team also studies other major contributors to food borne illness, including E. coli, shigella, and salmonella.

“If you don’t look for them and assess, then you won’t be able to identify which factors are most important for infections and antibiotic resistance or define how Michigan differs from other regions,” she says.

That assessment is, in part, the goal of the Michigan Sequencing Academic Partnership for Public Health Innovation and Response, or MI-SAPPHIRE, a grant that MDHHS awarded Manning’s team last year. The MI-SAPPHIRE program also has support from the CDC.

Source: Matt Davenport for Michigan State University