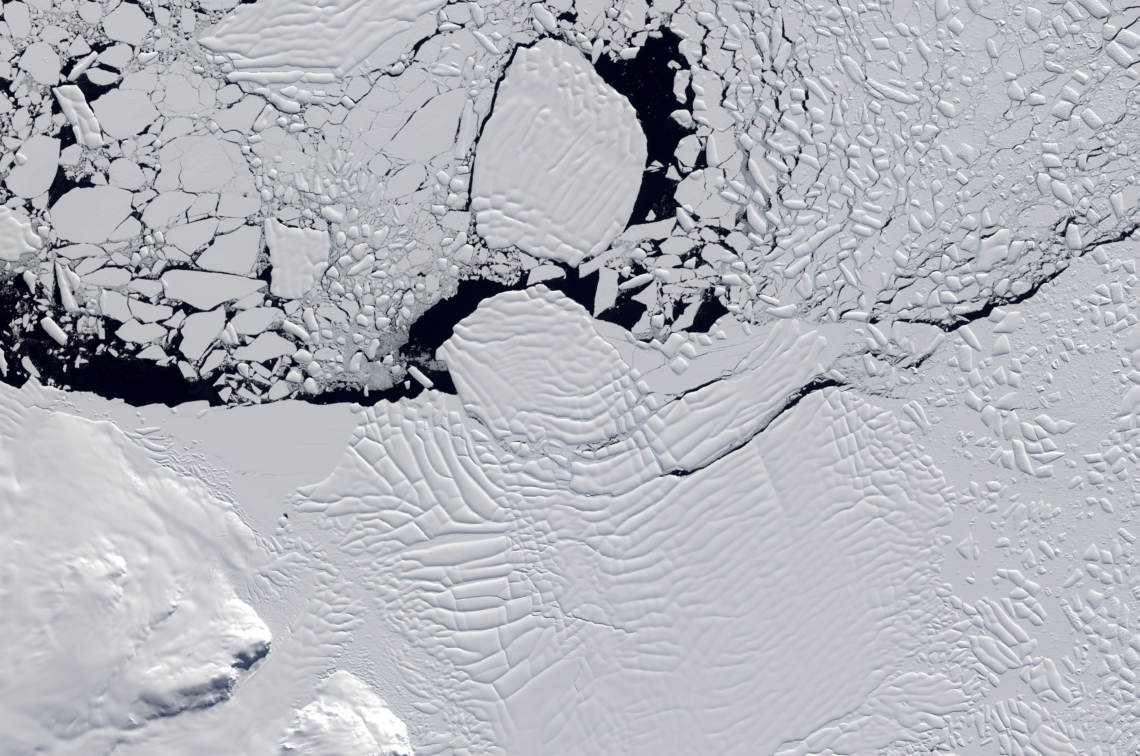

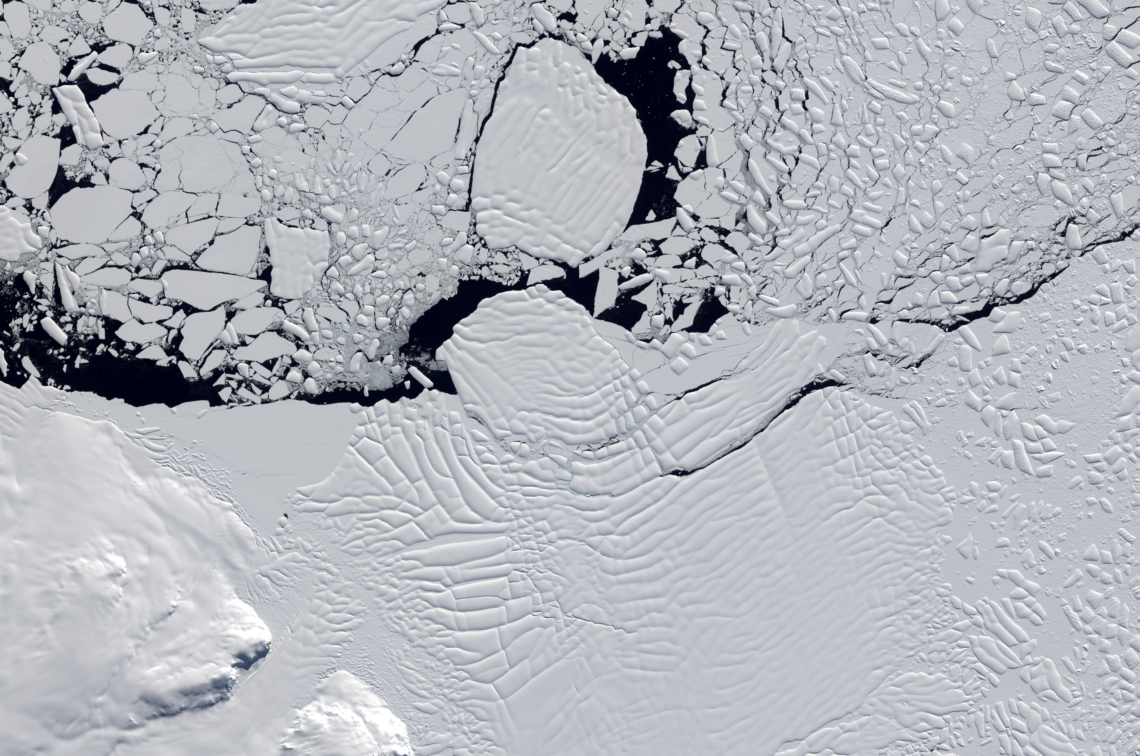

The pace and extent of ice destabilization along West Antarctica’s coast varies according to differences in regional climate, according to a new study.

The researchers combined satellite imagery and climate and ocean records to obtain the most detailed understanding yet of how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet—which contains enough ice to raise global sea level by 11 feet, or 3.3 meters—is responding to climate change.

The findings in Nature Communications show that while the West Antarctic Ice Sheet continues to retreat, the pace of retreat slowed in a key region between 2003 and 2015, driven by ocean temperatures, which were in turn caused by variations in offshore winds.

The marine-based West Antarctic Ice Sheet, home to the vast and unstable Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers, sits on an underwater landmass peaking 1.5 miles, or 2.5 kilometers, below the ocean’s surface.

Since the early 1990s, scientists have observed an abrupt acceleration in ice melt, retreat, and speed in this area, which is attributed in part to human-induced climate change over the past century.

Previous studies indicated that the observed changes could be the onset of an irreversible, ice-sheet-wide collapse, which would continue independently of any further climate-driven influence.

“The idea that once a marine-based ice sheet passes a certain tipping point it will cause a runaway response has been widely reported,” says lead author Frazer Christie at Cambridge University. “Despite this, questions remain about the extent to which ongoing changes in climate still regulate ice losses along the entire West Antarctic coastline.”

Using observations collected by an array of satellites, the new study found pronounced regional variations in how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet has changed since 2003 due to climate change, with the pace of retreat in the Amundsen Sea Sector, an area of West Antarctica facing the Pacific Ocean, having slowed significantly. That’s in contrast to the neighboring Bellingshausen Sea Sector, closer to the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, where glacier retreat accelerated during that time.

By analyzing climate and ocean records, the researchers linked these regional differences to changes in the strength and direction of offshore surface winds. When the prevailing westerly winds are stronger, more of the deeper, warmer ocean water reaches the surface and increases the rate of ice melt.

Researchers found that winds near the Amundsen Sector slackened between 2003 and 2015, because of a deepening of the Amundsen Sea low pressure system. This system is the key atmospheric circulation pattern in the region, and its center—near which changes in offshore wind strength are greatest—typically sits offshore of its namesake coast for most of the year.

The researchers found that the accelerated response of the glaciers flowing from the Bellingshausen Sea Sector can be explained by more constant winds there, causing more persistent ocean-driven melt.

Ultimately, the study illustrates the complexity of the competing ice, ocean, and atmosphere interactions driving shorter-term changes across West Antarctica, and raises important questions about how quickly the icy continent will evolve in a warming world.

“Ocean and atmospheric forcing mechanisms still really, really matter in West Antarctica,” says coauthor Eric Steig, a professor of earth and space sciences at the University of Washington. “That means that ice-sheet collapse is not inevitable. It depends on how climate changes over the next few decades, which we could influence in a positive way by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.”

And while the strength of the low-pressure cell in the Amundsen Sea is not necessarily tied to levels of greenhouse gases—itself an active area of study—the system’s influence shows that even the West Antarctic ice sheet is sensitive to weather and climate shifts.

Results show that changes in ocean, driven by changes in the winds, can slow down and even reverse the loss of ice, Steig says. But he points out that the effect is local and unlikely to last for more than a few decades.

“Only the most aggressive reductions in greenhouse gas emissions can plausibly turn the situation around in the long term,” Steig says.

Additional coauthors are from the University of Edinburgh. Support for the study came from the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland; the Scottish Alliance for Geoscience, Environment and Society; the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation; the UK Natural Environment Research Council; the US National Science Foundation; the joint UK/US International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration project; and the European Space Agency.

Source: University of Washington