Share this

Article

You are free to share this article under the Attribution 4.0 International license.

A 319-million-year-old fossilized fish skull holds the oldest example of a well-preserved vertebrate brain.

Scientists pulled the skull from a coal mine in England more than a century ago. The brain and its cranial nerves are roughly an inch long and belong to an extinct bluegill-size fish. The discovery opens a window into the neural anatomy and early evolution of the major group of fishes alive today, the ray-finned fishes, according to the study in Nature.

The serendipitous find also provides insights into the preservation of soft parts in fossils of backboned animals. Most of the animal fossils in museum collections were formed from hard body parts such as bones, teeth, and shells.

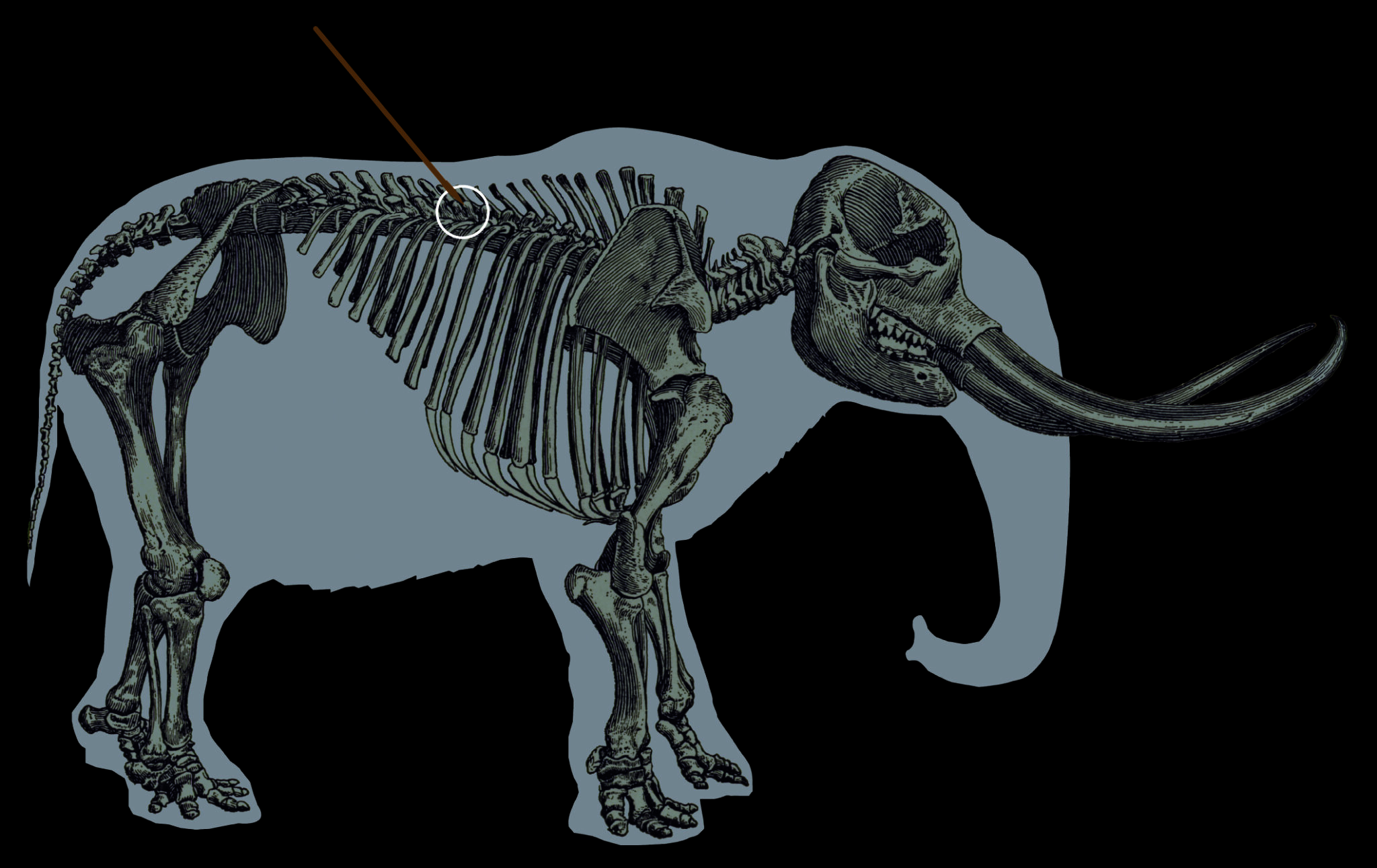

The CT-scanned brain analyzed for the new study belongs to Coccocephalus wildi, an early ray-finned fish that swam in an estuary and likely dined on small crustaceans, aquatic insects, and cephalopods, a group that today includes squid, octopuses, and cuttlefish. Ray-finned fishes have backbones and fins supported by bony rods called rays.

When the fish died, the soft tissues of its brain and cranial nerves were replaced during the fossilization process with a dense mineral that preserved, in exquisite detail, their three-dimensional structure.

“An important conclusion is that these kinds of soft parts can be preserved, and they may be preserved in fossils that we’ve had for a long time—this is a fossil that’s been known for over 100 years,” says senior author Matt Friedman, a paleontologist and director of the Museum of Paleontology at the University of Michigan.

Is this really a brain?

“Not only does this superficially unimpressive and small fossil show us the oldest example of a fossilized vertebrate brain, but it also shows that much of what we thought about brain evolution from living species alone will need reworking,” says lead author Rodrigo Figueroa, a doctoral student who did the work as part of his dissertation, under Friedman, in the earth and environmental sciences department.

“With the widespread availability of modern imaging techniques, I would not be surprised if we find that fossil brains and other soft parts are much more common than we previously thought. From now on, our research group and others will look at fossil fish heads with a new and different perspective.”

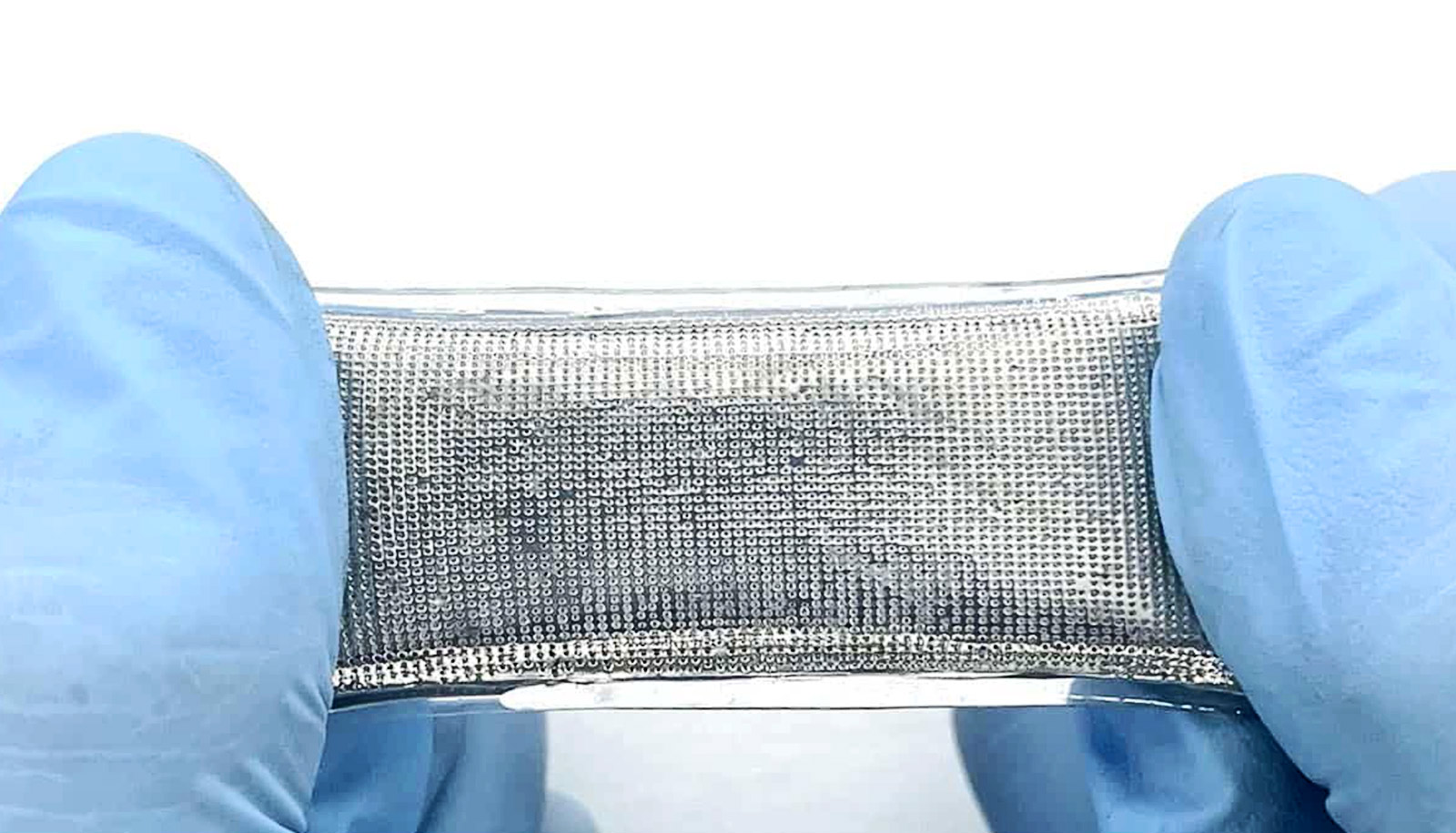

The skull fossil from England is the only known specimen of its species, so only nondestructive techniques could be used during the study.

The work on Coccocephalus is part of a broader effort by Friedman, Figueroa, and colleagues that uses computed tomography (CT) scanning to peer inside the skulls of early ray-finned fishes. The goal of the larger study is to obtain internal anatomical details that provide insights about evolutionary relationships.

In the case of C. wildi, Friedman wasn’t looking for a brain when he fired up his micro-CT scanner and examined the skull fossil.

“I scanned it, then I loaded the data into the software we use to visualize these scans and noticed that there was an unusual, distinct object inside the skull,” he says.

The unidentified blob was brighter on the CT image—and therefore likely denser—than the bones of the skull or the surrounding rock.

“It is common to see amorphous mineral growths in fossils, but this object had a clearly defined structure,” Friedman says.

The mystery object displayed several features found in vertebrate brains: It was bilaterally symmetrical, it contained hollow spaces similar in appearance to ventricles, and it had multiple filaments extending toward openings in the braincase, similar in appearance to cranial nerves, which travel through such canals in living species.

“It had all these features, and I said to myself, ‘Is this really a brain that I’m looking at?’” Friedman says. “So I zoomed in on that region of the skull to make a second, higher-resolution scan, and it was very clear that that’s exactly what it had to be. And it was only because this was such an unambiguous example that we decided to take it further.”

Fish evolution

Though preserved brain tissue has rarely been found in vertebrate fossils, scientists have had better success with invertebrates. For example, the intact brain of a 310-million-year-old horseshoe crab was reported in 2021, and scans of amber-encased insects have revealed brains and other organs. There is even evidence of brains and other parts of the nervous system recorded in flattened specimens more than 500 million years old.

The preserved brain of a 300-million-year-old shark relative was reported in 2009. But sharks, rays, and skates are cartilaginous fishes, which today hold relatively few species compared to the ray-finned fish lineage containing Coccocephalus.

Early ray-finned fishes like Coccocephalus can tell scientists about the initial evolutionary phases of today’s most diverse fish group, which includes everything from trout to tuna, seahorses to flounder.

There are roughly 30,000 ray-finned fish species, and they account for about half of all backboned animal species. The other half is split between land vertebrates—birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians—and less diverse fish groups like jawless fishes and cartilaginous fishes.

The Coccocephalus skull fossil is on loan to Friedman from England’s Manchester Museum. It was recovered from the roof of the Mountain Fourfoot coal mine in Lancashire and was first scientifically described in 1925. The fossil was found in a layer of soapstone adjacent to a coal seam in the mine.

Though only its skull was recovered, scientists believe that C. wildi would have been 6 to 8 inches long. Judging from its jaw shape and its teeth, it was probably a carnivore, Figueroa says.

When the fish died, scientists suspect it was quickly buried in sediments with little oxygen present. Such environments can slow the decomposition of soft body parts.

In addition, a chemical micro-environment inside the skull’s braincase may have helped to preserve the delicate brain tissues and to replace them with a dense mineral, possibly pyrite, Figueroa says.

Evidence supporting this idea comes from the cranial nerves, which send electrical signals between the brain and the sensory organs. In the Coccocephalus fossil, the cranial nerves are intact inside the braincase but disappear as they exit the skull.

“There seems to be, inside this tightly enclosed void in the skull, a little micro-environment that is conducive to the replacement of those soft parts with some kind of mineral phase, capturing the shape of tissues that would otherwise simply decay away,” Friedman says.

Skull scans

Detailed analysis of the fossil, along with comparisons to the brains of modern-fish specimens from the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology collection, revealed that the brain of Coccocephalus has a raisin-size central body with three main regions that roughly correspond to the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain in living fishes.

Cranial nerves project from both sides of the central body. Viewed as a single unit, the central body and the cranial nerves resemble a tiny crustacean, such as a lobster or a crab, with projecting arms, legs and claws.

Notably, the brain structure of Coccocephalus indicates a more complicated pattern of fish-brain evolution than is suggested by living species alone, according to the authors.

“These features give the fossil real value in understanding patterns of brain evolution, rather than simply being a curiosity of unexpected preservation,” Figueroa says.

For example, all living ray-finned fishes have an everted brain, meaning that the brains of embryonic fish develop by folding tissues from the inside of the embryo outward, like a sock turned inside out.

All other vertebrates have evaginated brains, meaning that neural tissue in developing brains folds inward.

“Unlike all living ray-finned fishes, the brain of Coccocephalus folds inward,” Friedman says. “So, this fossil is capturing a time before that signature feature of ray-finned fish brains evolved. This provides us with some constraints on when this trait evolved—something that we did not have a good handle on before the new data on Coccocephalus.”

Comparisons to living fishes showed that the brain of Coccocephalus is most similar to the brains of sturgeons and paddlefish, which are often called “primitive” fishes because they diverged from all other living ray-finned fishes more than 300 million years ago.

Friedman and Figueroa are continuing to CT scan the skulls of ray-finned fish fossils, including several specimens that Figueroa brought to Ann Arbor on loan from institutions in his home country, Brazil. Figueroa says his doctoral dissertation was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic but is expected to be completed in summer 2024.

Friedman and Figueroa says the discovery highlights the importance of preserving specimens in paleontology and zoology museums.

“Here we’ve found remarkable preservation in a fossil examined several times before by multiple people over the past century,” Friedman says. “But because we have these new tools for looking inside of fossils, it reveals another layer of information to us.

“That’s why holding onto the physical specimens is so important. Because who knows, in 100 years, what people might be able to do with the fossils in our collections now.”

The study includes data produced at University of Michigan’s Computed Tomography in Earth and Environmental Science facility, which is supported by the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts.

Sam Giles of London’s Natural History Museum and the University of Birmingham is a senior author of the study. Additional coauthors are from the University of Chicago and the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology.

Source: University of Michigan